MoMA and Family BBQ

By EricMesa

- 10 minutes read - 2033 wordsOn my Father’s Day Weekend visit to NYC I finally got to see some MoMA exhibits I’d wanted to see for months. First off was a Picasso exhibit called “Variations”. Ever since my parents took me to the Dali Museum in St Petersburg, FL six years ago, I’ve been very interested in painters – especially artists from the 1930s-1950s and the surrealist and associated movements. Also, as a person of Spanish heritage, I’ve had a special interest in artists from the region. So I was very excited to see this Picasso exhibit.

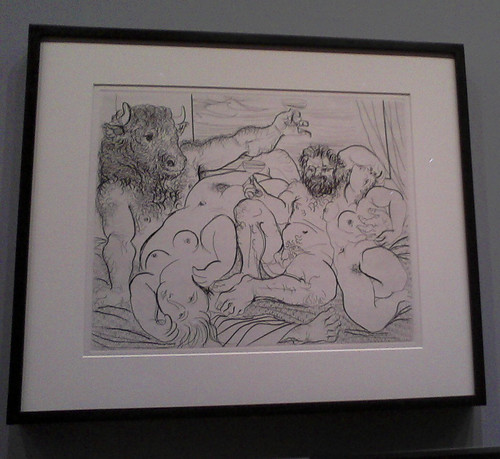

When I first walked into the exhibition space, I was initially disappointed to read that this exhibit was focusing not on his paintings, but rather his pencil and printmaking works. After going through the exhibit I was very happy to have seen this side of his art that I had never experienced before. A good part of one room was dedicated to his series featuring a minotaur representing lust and the id side of sexuality.

[caption id="" align=“aligncenter” width=“500” caption=“My favorite photo from the series. I just love the playful style and the audacity of the image.”]  [/caption]

[/caption]

I found this series to be both playful (because of the art style) and highly symbolic. Unlike the extreme abstract art we sometimes see with post-modern art, Picasso’s symbols were clear. Before I read the caption explaining the series, it was quite obvious to me that the minotaur represented unrestrained sexuality. I enjoyed being able to understand the art pieces without having to first read about what the heck it was I was looking at.

One of the most interesting aspects of this exhibit is that it showcased most of Picasso’s least surreal/cubist/etc artwork. It was often pretty obvious what it was you were looking at. The following sentiment will probably reveal my boorishness when it comes to art, but frankly anyone can create cubist art. It seems to simply require forgetting everything you know about 3D and putting the back and front of an object on display at the same time. Kids often do this when they’re learning how to draw. (this is not to take away from the skill required to properly paint it) But to see this artwork showed that Picasso was a master artist. His drawings reveal that he could draw and paint normally if he wanted to. That is, of course, how I define art – knowing the rules before you break them. So, a kid scribbling on paper is not art. But an artist scribbling on a canvas with a purpose will have the same result as a kid, but it is art. So to know that Picasso was not drawing weird simply because he didn’t know how to properly draw a face made me see him as an even greater artist.

On display were also a bunch of portrait drawings of each of his mistresses. Apparently each woman with whom he became involved sexually also became one of his muses. He made dozens of sketches of each of these women and they also appear in other works of art where they are not the only focus or maybe even not the primary focus. As I observed these, my mind wandered from the art to real life. What would it be like for his wife to have him not only involved with all these women, but sketching them and incorporating them into his art. Would she feel sad that she could not provide him all the inspiration he needed? Did she feel it was so brazen for him to create art from his mistresses?

And what of these other women. When they could no longer provide him with inspiration and he tossed them aside for another, did they feel spurned? Did they feel used as they became part of his art and he earned money from their likenesses? I also wondered how they felt about his portraits. While some of the portraits were drawn in the traditional manner, many of them are cubist or surreal. I know, from the captions at the museum, that at least one of these women was a surrealist artist. She would have appreciated the distortion in his work, but what of the others? Did they find it weird or grotesque to be depicted in this manner?

Above I mentioned the playfulness on display in some of the art from this exhibit. Another series which exemplified that spirit of play (but which I did not photograph) was a series of drawings of a bull. This series is Picasso playing a reductionist game to see how basic he can make a bull with us still recognizing it as a bull. Each successive work has less and less detail. (by analogy, the end result is similar to a stick figure as representative of a person) This is playful on an intellectual level and it tickled my brain to see it. But what I found extra funny was that amongst the details Picasso deemed essential to know it was a bull (horns, almond head, large body) were large testicles and a penis.

As I ascended the stairs to my final destination on the sixth floor, I stopped to see a photographic exhibit consisting entirely of female photographers. The first impression I got while walking around the exhibit was that there appeared to be no inherent difference between having a male or female behind the lens. In other words, there was nothing on the surface that screamed out, “This was taken by a woman!” On closer inspection I found a few threads that ran through the exhibit, but, at least in the way this exhibit was curated, they were only the faintest of threads. One such thread was an examination of the female condition — using the photograph to show others what it means to be a woman. Often this was very subtle, although there was one piece by an artist featuring a series of self-portraits that appeared to document her life in an abusive relationship. The images were brutal without being overly graphic and it made me hope that it was staged and not photodocumentary. Another thread, again, very faint as it only encompassed a few of the photographs on display, was that of motherhood. The piece that stood out to me here was a series of portraits of the photographer’s daughter — one per year (only a subset of these were on display). Each was taken on a chair by a window. It was interesting to see the expression on the face go from childlike happiness to “ugh, I have to do this again!” to appreciation of the effort as she grew. The most profound was the last photograph chosen for this exhibit in which the daughter is now pregnant — presumably with a daughter of her own.

As expected, there were far fewer images of the female form than in a male photographic exhibit. Although there have been exceptions, throughout photographic history most images of the female form have been by male photographers. (As was the case with painting) Nor were there many images of the male form — it appears to be more off limits — perhaps exposing an undercurrent of sexism in the art world? In my surveys of photographic history and in what I’ve seen of paintings in museums, males have seldom been depicted nude. Far more likely has been the depiction of the nude or semi-nude female form. In fact, masculinity often is masked, as in the case of Picasso above, in the form of a minotaur, centaur, or other mythological half-man create. Part of this appears to be changing — at least from what I can tell on flickr. If females are not taking more portraits of the female form with other models, there is a proliferation of self-portraiture of the female form on flickr. This may, however, simply be a symptom of our narcissistic culture colliding with our voyeuristic culture. The female form will attract a much greater audience to someone’s photostream. Still, it removes at least one layer of exploitation to have the woman photographing the naked woman. But, as in other fields (pornography, music videos, film, etc) a case can be made that the woman is simply still functioning in the same world under the same pressures even if it is for a female master. Suffice to say, it’s a complicated issue and one that will not be explored any further in this post.

My main draw to the museum was a comprehensive exhibit of the work of photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. This exhibit occupied all of space on the top floor that was available for public viewing. (Another area was under construction for a new exhibit) This collection of photos was amazingly vast. The space was arranged to take the visitor through Cartier-Bresson’s career in a roughly chronological order. The chronology was broken up a bit in order to divide his photojournalistic work into different categories —mostly on geographical boundaries.

The bulk of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photojournalistic work was accomplished in the 1930s and 1940s. His photographs appeared in all the important photojournalistic magazines of the world at that time. On display were magazine photo essays from American and French magazines. Given that commercial aviation was still a novelty during this time, it is astonishing that Henri travelled to so many places to bring back photographs for his assignments. Photographs on display included locales as diverse as America, England, Communist Russia (one of the first non-communists allowed to photograph there), Shanghai, China before and after the Maoist revolution, and Spain before, during, and after the 1930s civil war. Even today, with all our modern airplanes and relatively cheap flights (especially compared to the 1930s) most people don’t get to visit so many countries. But, back then before the Internet, his photographs (along with other photographers of the time) were all that Americans would get to see and know about places like China. It probably conferred both a great responsibility to properly represent the countries he was photographing and a feeling of great privilege to travel to all these places. In addition to the photojournalism work, he had photographs of some of the most famous people of his time including Jean Paul Sartre. They also had photographs of women and his capture of feminine beauty.

It was interesting to see the photos in a museum setting. For the most part, museums are associated with art (especially when the museum is named the “museum of modern art”). While photojournalism can produce photographs that people would conventionally consider art, I do not believe that 99.9% of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs would fulfill those requirements. They are great photos, often capturing a great moment. Most of the time they also exhibit great technique. To me, this makes them art. But they are not artsy photos. And that is what had my wife feeling a bit disappointed. She was expecting a great art photographer – I had told her nothing about Cartier-Bresson other than that he was a famous and heralded photographer. I guess, when it comes down to it, she found the photos too ordinary. To put it another way, she asked why my similar photographs of NYC life were not on display on the walls at MoMA. What made his photograph of a man in Shanghai haggling at the market different from one a tourist might take today that was of the same technical merits. I could not answer that question. He was, no doubt, a great photographer – as I mentioned, his photographs both capture that special moment and display perfect technique. But in modern times we are inundated with photographers of similar skill on flickr. Who will decide if one of them will end up in MoMA in the future?

That evening I went to dinner at Danielle’s cousin’s house. I was able to get some shots of people interacting with all the kids. They’re all in the 3-6 year range so they make nice, cute subjects. Here are a few photos from the evening.

Finally, we all went to see Toy Story 3 (in 2D) at a 2230 showing. I will discuss this in my next blog post.

- Art

- Bbq

- Flickr

- Henri-Cartier-Bresson

- Moma

- Museum-of-Modern-Art

- Nyc

- Photo-Essay

- Photojournalism

- Picasso

- Women